By Blake Adams

There is a Santa Claus. He was a fourth-century bishop in modern Turkey during some of the most interesting times in Christian history. He survived the Diocletian persecution (we can assume he was tortured for his faith), lived through the vitalization of the Church under Constantine, and if he did not attend the Council of Nicaea (a debated point: he is not mentioned among the attendees), was apparently much involved in the campaign against Arianism. This is about all we can say of the “historical” Santa Claus, who at the time went by Nicholas of Myra. Though as far as names go, Santa Claus is St. Nicholas, as the former is simply the Americanization of Sinter Klaas, itself the shortened form of Sint Nikolaas, the Dutch translation of Saint Nicholas. (It was Dutch Catholics who (re?)introduced the saint to Protestant America in the eighteenth century.)

This time of year, we often see the “fantastical” and “corporate” Santa Claus opposed to the “historical” and “traditional” St. Nicholas, with an implicit call to Christians to reject the former and embrace the latter. To be sure, there are regrettable differences, even aside from the sleigh, elves, and toy factory in the North Pole. The old Nicholas was an ascetic who, legend has it, fasted on Wednesdays and Fridays even as a nursing baby. Contrast this with Santa Claus whose diet of milk and cookies endows him with “a little round belly” that “shook when he laughed like a bowlful of jelly.” What’s more, the earliest descriptions of Nicholas cast him in the drab, black garb of the peasant folk, not festive red. Even his beard was black.

But historical honesty forces us to admit there are many Santas, not one “traditional” St. Nicholas. The saint has always been more legend than history, whatever basis that legend may have in history. The earliest biographical details about him appear in a hagiography written nearly half a millennium after his death. As his popularity grew over the centuries, new stories and accessories were added. By the Renaissance, Nicholas was one of the most popular saints in Europe, but there were almost as many Nicholases as there were countries in Christendom. The American version (for that is what Santa Claus is; the British would adapt him to their own Father Christmas after the fact) who appeared in the eighteenth century as Santa Claus was simply a synthesis of a number of these. So rather than speak of the “historical” Nicholas or attempt to depose our native version as an imposter, I’d rather retrieve the earlier legend to reform the modern one. Santa Claus, I contend, is simply the American St. Nicholas, and a more faithful iteration than we might at first realize.

Everything essential about St. Nicholas is found in his most famous story. The oldest version is told by Michael the Archimandrite in AD 700/710. It opens with a father so financially desperate he has resolved to sell each of his three daughters, one by one, into prostitution—a regrettably common recourse in the ancient world. The prospect pained the father greatly, but since he could not afford dowries for his daughters, no suitor would take them. To him, prostitution was preferable to destitution: at least this way, the girls would have means to live. The night before he was to sell his first daughter, however, a bag of money in exactly the amount needed for a dowry appeared on the floor of his home overnight. It had been tossed through the window while he slept. In later versions of the story, the money was thrown down the chimney or stuffed inside stockings hung over the fireplace to dry. The father couldn’t believe his fortune! He married off the daughter immediately. The next night, another moneybag appeared for the second daughter. On the third night, the father was ready. Eager to identify his patron, he kept vigil so when he heard the clatter of coins on the floor, he dashed out the door and tackled the backwards-burglar. It was none other than his own bishop, Nicholas—who pleaded that his good deed be kept a secret. Instead, this story found such fame, it became Nicholas’s calling card: to pick him out in an icon of mitred saints, you need only look for the bishop holding three moneybags (or three gold spheres or plates). Here we already see the essence of the covert night-time gift-giver so familiar to us.

This story is exceptional for a hagiography (or, for that matter, Santa Claus). These tend to trade in spectacular miracles, such as Peter raising a smoked tuna back to life (Acts of Peter 13), or outright fantasy, as when Anthony the Great met a centaur (Jerome, Life of Paul 7). But in this story, there are no miracles, no fancies. This makes Nicholas relatable, but the absence of the miraculous actually heightens the demands the story places on the reader: anyone can do the sort of charity work done by Nicholas, even if they are not as rich as Nicholas, because his goodness is ordinary goodness, not miraculous goodness.

A notable lesson from this story is Nicholas’s attitude about gift-giving. For many ancient saints, like Anthony the Great, giving money to the poor was a form of renunciation: a way to separate oneself from the systems of worldliness which lead to spiritual death. Money was not evil (otherwise, he’d have burned it rather than given it away) but a sign of worldly glory the saint gladly exchanged for heavenly treasures. Nicholas shared this outlook, but he understood the end of almsgiving was not so much separation from the world as charity. For him, the primary purpose of almsgiving was to bless. So he did not endow his riches on a faceless mass called “the poor.” He favored a personal approach. He knew to whom he gave, and every gift fit exactly the need in order to produce the maximum blessedness. This required vigilance: he had to watch his community carefully for such opportunities. But it is also a form of almsgiving we can all imitate. Not everyone can be a St. Anthony, but anyone can be a St. Nick.

Michael wrote his biography of St. Nicholas on the occasion of his Feast Day, and indicates this celebration was occurring as the Church was anticipating the Feast of the Nativity. While the precise date for Nicholas Day is not given, there is no reason to suppose it wasn’t December 6. At any rate, we see that Nicholas’ association with Christmas was established early. He is the first saint we meet on our journey through Advent, and his generous and gift-giving character sets the tone for the season, then as now.

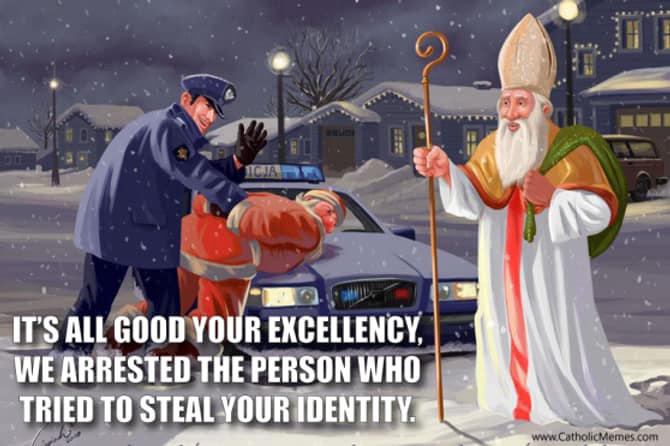

Not all features of the American St. Nicholas should be kept. In fact, some mustn’t be. But despite these, I contend Santa Claus retains the spirit of his predecessors. He needs reforming (many of him do), but let’s reclaim him rather than abandon him as a casualty of Coca-Cola’s marketing campaigns. I doubt many of us hold much real fondness for the saccharine, cartoonish, commercialized, Hollywood cliché, anyway. The best and most loveable Santa is the one we never see, the one evidenced by what he leaves behind. The real delight of Santa Claus is that he is the culture’s last holy fool. He does everything in accordance with charity, but in reverse: He stages a home invasion, but leaves treasures rather than takes them. There is wisdom even in his topsy-turvy approach to entering homes. G.K. Chesterton reminded us a century ago that by reversing things, Santa Claus shows us the right way up: he does not come through the front door “like a gentleman” because, to one so heavenly minded, the chimney is obviously the front door, for it is the door fronting heaven. Our own Santa Claus has not lost the capacity to lift up our eyes.

needs reforming (many of him do), but let’s reclaim him rather than abandon him as a casualty of Coca-Cola’s marketing campaigns. I doubt many of us hold much real fondness for the saccharine, cartoonish, commercialized, Hollywood cliché, anyway. The best and most loveable Santa is the one we never see, the one evidenced by what he leaves behind. The real delight of Santa Claus is that he is the culture’s last holy fool. He does everything in accordance with charity, but in reverse: He stages a home invasion, but leaves treasures rather than takes them. There is wisdom even in his topsy-turvy approach to entering homes. G.K. Chesterton reminded us a century ago that by reversing things, Santa Claus shows us the right way up: he does not come through the front door “like a gentleman” because, to one so heavenly minded, the chimney is obviously the front door, for it is the door fronting heaven. Our own Santa Claus has not lost the capacity to lift up our eyes.

—–

¹ Michael the Archimandrite, Vita per Michaelem, 4, quoted in Adam C. English, The Saint Who Would Be Santa Claus: The True Life and Trials of Nicholas of Myra (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2012), 33.

² Michael, Vita per Michaelem, 24, quoted in English, Saint Who Would Be Santa Claus, 92.

³ Michael, Vita per Michaelem, 1, quoted in English, Saint Who Would Be Santa Claus, 28.

4 G.K. Chesterton, Manalive (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2000), 88. First published 1912.

Blake Adams (M.A., Wheaton) is a copy editor at Logos Bible and a trained historian. He serves as Lead Sacristan at Church of the Resurrection and is enrolled in St. Paul’s House of Formation. You can find Blake on Substack.

Blake Adams (M.A., Wheaton) is a copy editor at Logos Bible and a trained historian. He serves as Lead Sacristan at Church of the Resurrection and is enrolled in St. Paul’s House of Formation. You can find Blake on Substack.

Images:

1) Top photo of Santa by krakenimages on Unsplash

2) Bishop Nicholas photo by Jaroslav Čermák – Galerie Art Praha, Public Domain, Wikipedia Commons.

3) Dowry for the Three Virgins: Gentile da Fabriano – The Yorck Project (2002) 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei (DVD-ROM), distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH. ISBN: 3936122202.

4) A popular internet meme: #